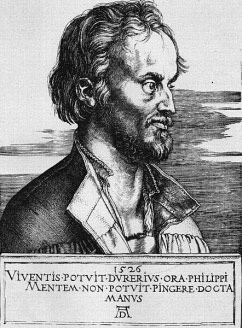

Philip Melanchthon, Renewer of the Church 19 April 1560

Seleccionar idioma español/Choisissez la langue français

Philipp Schwartzerd was born in Bretten, Germany, in 1497. After the death of his father in 1508, his education was supervised by his great-uncle, Johann Reuchlin, the most distinguished (non-Jewish) Hebrew scholar of his day, and author of De Rudimentis Hebraicis, a dictionary and grammar of the Hebrew language that appeared in 1506 and became the basis of modern Hebrew scholarship. (Earlier, in 1478, when he was 23 years old, he had published Vocabularius Breviloquus, a concise Latin dictionary that was widely used for many years.) In 1509 the Emperor ordered that all Hebrew literature except for the Old Testament should be destroyed, and Reuchlin devoted most of the rest of his life (he died in 1522) to fighting this decree.

Reuchlin took care that his great-nephew Philipp should receive a good classical education, and changed his surname from Schwartzerd to Melanchthon. (Both names mean "black earth." "Schwarz" means "black," and so does "melan," as in "melanin" or "melancholy"; "Erd" means "earth," and so does "chthon," as in "chthonic" or "autochthon".) In 1511 (at the age of 14) Philipp received his B.A. from the University of Heidelberg, and his M.A. from Tuebingen three years later. In 1518 he published Institutiones Grammaticae Graecae (Basics of Greek Grammar), the first of many school texts that he would eventually write. His knowledge of Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and the liberal arts won him the enthusiastic praise of the Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus.

In 1518 Philipp was hired by the University of Wittenberg as its first Professor of Greek. He repidly became one of the most prominent of its lecturers. He rose every day at 2am for prayer, study, and writing (he had produced six books before arriving at Wittenberg, and in the next four years turned out seven more), and began his first public lecture of the day at 6am, often to classes of 600 students. Within four days after his arrival, he gave a speech "On the Improvement of Studies," setting out a program of study based on the classics and the Fathers of the Church as a basis for Christian education, for the renewal of theological studies and the improvement of society. He soon met Martin Luther, and the two became fast friends. Melanchthon's cool, organized, disciplined habits of thinking and writing formed the perfect complement to Luther's brilliant but impulsive thinking and his fiery, emotional rhetoric. In 1519, when Luther debated at Leipzig with Johann Eck, the pope's representative, Melanchthon was Luther's second, and subsequently exchanged a series of pamphlets with Eck that established his reputation as a principal spokesman for the Evangelical position. In 1521, his lectures on St Paul's Epistle to the Romans were published under the title Loci Communes Rerum Theologicarum (Notes on Theology— literally, Common Places of Things Theological). It was the first systematic statement of Evangelical theology, and it became an instant best-seller, going into 18 Latin editions alone (plus numerous translations) within four years. Eventually, the University of Cambridge made it required reading, and Queen Elizabeth of England virtually memorized it. To Melanchthon's grief, it brought about a permanent break with his beloved great-uncle, who remained a loyal adherent of the Papal position.

Melanchthon also gave a series of lectures in 1521 on St Paul's Epistles to the Corinthians, but declined to publish them. Luther stole the manuscript and sent it to the printers (naming Melanchthon as author, of course). He did the same thing in 1523 with Melanchthon's lectures on the Gospel of St. John.

Although he did not lack theological training, Melanchthon was never ordained. He was known in his day as an educator. In 1528 he wrote a manual for school inspectors, Unterricht Der Visitatoren (Instructions for Visitors), outlining a plan of organization and curriculum for a preparatory school. At least 56 cities asked him to visit them and help them organize their public schools. He helped to found universities at Marburg, Koenigsberg, and Jena, and to re-organize the existing universities at Greifswald, Wittenberg, Cologne, Tuebingen, Leipzig, Heidelberg, Rostock, and Frankfurt der Oder. He became known as the Schoolmaster of Germany, and well into the twentieth century the German educational system, both university and pre-university, was run with little variation from the structure he had given it.

In 1520, he married the daughter of the mayor of Wittenberg, and they had two sons and two daughters.

Melanchthon was of a conciliatory spirit, always trying to find and emphasize areas of agreement with fellow Christians. Thus, in 1530, when he drew up the Augsburg Confession (in Latin the Confessio Augustana), a statement in 28 Articles of the Lutheran position, to be presented to the Emperor, he began by stating that the Lutherans differed from Rome in no article of the Faith, and affirming in the first 21 Articles some of the many doctrines that the two sides both believed. In the article on the Mass, he wrote that Lutherans had been falsely accused of abolishing the Mass, and that, on the contrary, they celebrated it regularly and with great devotion, but that they had added hymns and prayers in the German language, by way of instructing the people, so that they might better understand the significance of the service. Only in the latter part of the Confession, the last 7 Articles, does he discuss what he calls "reforms of abuses." The seven Articles are devoted to:

1. Communion in one kind. The Romanists had recently introduced the custom of

giving only the consecrated Bread to the congregation, and reserving the Chalice for

the celebrant alone.

2. Clerical celibacy. The Romanists had required that all priests be unmarried.

No one claimed that this was a commandment of God; it had never been required in the

East; and Rome permitted a married priesthood in Eastern-rite

churches that recognized the

authority of the Pope.

3. The payment of fees for the celebration of the Liturgy as an expiatory sacrifice

for the sins of a designated person. Connected with this we have the whole question

of the sense in which Christ is sacrificed when the Lord's

Supper is celebrated. Theologians officially delegated by the Roman and Lutheran Churches to meet and discuss the

matter have declared that the positions of the two groups are compatible, but in the heat

of 16th-century controversy this was not obvious.

4. Compulsory confession. The Lutherans certainly expected their people to go

to confession regularly, and said so in the Augsburg Confession. The difference,

as I understand it, is that the Roman rules were that the penitent must name all the

deliberate sins that he has committed and not previously confessed, so that the emphasis

is on the list of misdeeds. Deliberately omitting to mention a deliberate sin invalidates

the confession. If you honestly forget to mention one, then the confession is still

valid, but you must mention that sin the next time you go to confession. In theory, this

means that anyone intending to make a good confession, and honestly trying to remember all

his past sins, has no cause for worry about forgetting something. In practice, many sincere

and troubled penitents were frantic with worry over the possibility that they had

forgotten something. Luther, on the other hand, said that we come before God, not to list

our sins, but to acknowledge our sinfulness. "The physician does not need to catalog

every pustule on the body before diagnosing smallpox." He accordingly told the penitent to

acknowledge that he was a sinner, in need of God's grace, and then to name the sins that he was

principally aware of. It is still understood, of course, that omitting a sin because you do

not repent of it and have no intention of stopping it means that you do not really wish God

to be the Lord of your life, and that you have simply added a fraudulent confession to your

other sins.

5. Human institutes designed to merit grace. The reference here is to the idea

that (for example) participating in the fasts prescribed by the Church would automatically

be rewarded by a gift of God's grace. No one was denying, as far as I know, that

fasting can be spiritually beneficial.

6. Abuses connected with monastic discipline.

7. Arrangements by which bishops doubled as officials of the secular government,

and exercised authority as magistrates and princes.

The Romanists naturally published a rebuttal to the Augsburg Confession, and Melanchthon wrote an Apology of the Augsburg Confession (Apology=Defense) in 1531. The Apology, along with the Confession itself, is one of the great statements of faith of the Lutheran Tradition. The Confession, the Apology, the Catechism, the Schmalkald Articles, and the Formula of Concord are usually published together in a single book, called The Book of Concord. An appendix to the Schmalkald Articles, written by Melanchthon, deals with the Papacy. On the one hand, it denies that the Papacy is of divine institution, and provides theological and historical arguments for this position. On the other hand, it states that, for the peace and unity of the Church, it may be judged expedient that the Bishop of Rome should be conceded a position of leadership and authority, provided that the essential doctrines of the faith, including the doctrine of justification by faith, are safeguarded.

The Augsburg Confession declares that, in the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper, the true Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ are received "by the mouth." Calvinists spoke instead of feeding on Christ in the heart, carefully affirming that this occurred in a special way in the Sacrament, and was not simply something that happens whenever a devout Christian thinks of Calvary. Calvinists were reluctant to accept the wording of the Augsburg Confession, and so in 1540 Melanchthon drew up a revised version, in which the statement in Article 10 about the presence of Christ in the Sacrament was intended to satisfy all parties. However, his fellow Lutherans regarded this as a sell-out, and today Lutherans in general pledge their adherence to "the unaltered Augsburg Confession," meaning the 1530 version, before Melanchthon "watered it down."

Luther died in 1546. In 1547 the Lutherans were defeated in a major battle at Muehlberg, and were in danger of being suppressed altogether throughout Germany. Melanchthon, for the sake of peace, proposed a settlement which would preserve the essentials of the Faith as understood by the Lutherans, but would make concessions on ritual and practice and on non-essention matters of doctrine. For this, he was again denounced as a traitor by many Lutherans.

On any short list of the men who, in the troubled years of the sixteenth century, undertook to serve Christ by working for a spiritual renewal in His Church (and I am here thinking both of those who defended the Papacy and of those who attacked it), Melanchton's name deserves to be included. He died in Wittenberg, 19 April 1560, and was buried beside Luther.

Although most hig- school history texts date the beginning of the Lutheran movement from 1 November 1517, when Martin Luther published his Ninety-Five Theses, most Lutheran scholars date it from 25 June 1530, when the Lutheran leaders presented a formal statement of their beliefs to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his Diet (Parliament) at Augsburg. In April 1530 the Emperor summoned a conference to achieve religious unity among his people. Since Luther was under ban and could not attend, the Lutheran statement was drawn up by his colleague Philip Melanchthon and privately approved by Luther. The statement was presented in the hope of reaching some kind of peaceful agreement between the Lutherans and the adherents of the Pope, and it stresses the beliefs which the two sides had in common. It repudiates the notion of change for the sake of change, and (for example) denies the charge that the Lutherans wish to abolish the Mass, saying that the Mass continues to be celebrated among Lutherans, but with hymns and prayers included in German, in order that the people may clearly understand the significance of what is being done.

It is divided into 28 Articles, with the first 21 giving a summary of what Lutherans consider essential doctrine (with Article 20, "On Good Works" being a particularly long one), and the remaining seven devoted to "Abuses which have been Corrected."

The Augsburg Confession (using the word "confession" to mean "statement of faith" rather than "acknowledgement of guilt") was written in Latin and German editions, and presented to the Diet of Augsburg on 25 June 1530. It at once spread widely among Lutherans, with a Danish translation appearing in 1533 and an English one in 1536. A Greek version was prepared for use in dialogue with the East Orthodox churches. In more recent years, translations have been made into Chinese, Japanese, Hindi, Tamil, Swahili, Zulu, and Malagasy.

In the first few years, even apart from questions of translation, there were variations and expansions in some copies. In particular, in 1540, Melanchthon himself produced a version that was deliberately vague on some matters where Lutherans and Calvinists differed, in the hope of achieving unity with the Calvinists. Today, practically all Lutheran church bodies include in their charters a statement of adherence to the "The Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, the Athanasian Creed, and the Unaltered Augsburg Confession."

Other confessional statements in use among Lutherans, though not having the same authority as those just cited, include the Defense (Apology) of the Augsburg Confession (by Melanchthon), the Smalcald Articles (by Luther), the Small Catechism, the Large Catechism, the Formula of Concord, the Catalog of Testimonies, and the Visitation Articles. All these (together with the ones listed in the previous paragraph) are customarily bound together in a single volume called The Book of Concord.

written by James Kiefer

Almighty God, we praise you for the men and women you have sent to call the Church to its tasks and renew its life, such as your servant Philip Melanchthon. Raise up in our own day teachers and prophets inspired by your Spirit, whose voices will give strength to your Church and proclaim the reality of your kingdom; through your Son, Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.